PM Magazine interview with Bob Heil: The Night That Modern Live Sound Was Born

Interview with Bob Heil in December 2008 Performing Musician Magazine (offline).

Bob Heil & The Grateful Dead

Published in PM December 2008

One night in 1970, the Grateful Dead found themselves without a sound system or soundman, and Bob Heil found himself the man of the moment.

Dan Daley

It’s the kind of thing that physicists and palaeontologists dream about: being able to look back and determine the exact moment that a star or a dinosaur came into being. For the contemporary live sound business, that moment was the night of 2nd February 1970 at the Fox Theatre in St. Louis, Missouri. It’s about as good a story as it gets in an industry filled with great tales.

In 1970, the original jam band, the Grateful Dead, were about to take their career to the next level, transitioning from the fuzzily focused psychedelia of the 1960s to the more earthy ur-Americana of Workingman’s Dead and American Beauty, both of which were released that year. But even with those landmark records, the Dead routinely experienced mediocre record sales. Their popularity as a live band, however, was indisputable. Tens of thousands of rabid fans would converge at venues worldwide to gyrate through the Dead’s legendarily marathon concerts, some of which would go on for as long as six hours.

What they were listening to up to that point was a sound system developed in part and operated by someone well known to the counter-culture and law enforcement alike as either simply Owsley or Bear (real name Augustus Owsley Stanley III). In addition to his work as the Dead’s touring sound FOH mixer, Owsley had several interesting side careers. The most notable was as a chemist, though not of the sort that his father, a former governor of the state of Kentucky and former member of the US Senate, might have condoned. Owsley is estimated to have produced roughly five million ‘hits’ of LSD in the mid-1960s in San Francisco, the ground zero of hippiedom and the petri dish for the Grateful Dead.

Owsley, not unexpectedly, was plagued by criminal prosecutions (though in his defence it should be noted that when he began cooking the stuff in 1965 LSD was not yet illegal in the US). One condition of his being released pending drug charges was that he not leave the state of California. Unfortunately, New Orleans is very much not in that state. Owsley was arrested on a warrant one February night after a gig in the Big Easy, with police detaining him and most of the sound system there. The PA system that the Grateful Dead pulled up to the Fox Theatre with the next day consisted of a few wedge monitors that happened to have been luckily stored in the lorry carrying the guitar amps.

Enter Bob Heil

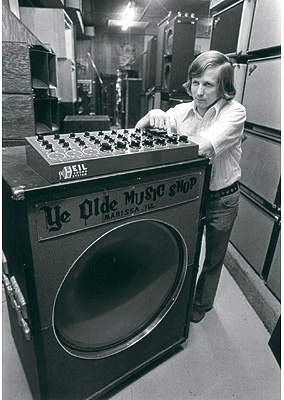

In one of the most serendipitous moments in rock history, someone at the Fox gave Dead guitarist Jerry Garcia the phone number for Bob Heil, who ran a music store in the remote St. Louis suburb of Marissa, Illinois. Heil, who at the age of 14 started his musical career as the house player of the Fox’s huge pipe organ, had taken a passion for ham radio and turned it into a career repairing guitar amplifiers and other things electronic, even as he continued playing the Fox’s grand organ and other gigs.

However, the electronics bug got the better of him and in 1966 he began experimenting with live sound systems, becoming the technician and occasional letter of gear to several venues around St. Louis, from auditoriums to bowling alleys, keeping the primitive and under-powered sound systems of the time (the Beatles had played Shea Stadium in New York in 1965 using only a Shure Vocalmaster PA system plugged into the baseball park’s announcement system) up and running.

But it was when the Fox Theatre let Heil take possession of their aging, but still massive Altec A-4 speaker cabinets that the beginnings of the modern live sound touring system began to come together. “The Fox Theatre had these huge Altecs that I got my hands on,” Heil recalls. “I was experimenting with amps and at first it was like a passionate hobby, like the radio, but I soon saw these guys coming in with these little columns under the impression that they were going to fill up a 20,000-seat hall. In 1968 there was nobody else doing what I was doing, so I felt that I had to build some kind of monster sound system for them.”

The system

The Grateful Dead at the Fox Theatre on February 2nd, 1970.

“Hey man, I heard you have a really big PA,” Heil remembers Garcia saying to him on the phone. It was. The Altec A-4 was the foundation slab for what would be an approximately 5ft-tall stack. Altec Lansing’s A-4 launched the famous Voice of the Theatre series, which put Altec Lansing at the forefront of film sound for 40 years after it debuted in 1945. It consisted of a large, ported low-frequency section with dual woofers, additionally front-loaded with a straight horn. Heil used JBL four-inch diameter 2482 mid-range compression drivers on the JBL 90-degree and 60-degree radial horns. He replaced the original 15-inch speakers with JBL D140s that used a four-inch aluminium voice coil, and the first 15-inch low-frequency transducer to make use of flat wire.

Atop that was an array of radial horns, four per stack. “That made a huge difference,” Heil exclaims. “No one was putting radial horns into PA systems; they were just doing speakers in columns, like the Vocalmaster. The horns are what give the system intelligibility — you can actually understand the lyrics.”

After that, four or six JBL 075 ring tweeters completed a stack that covered the frequency range from below 200Hz to well over 15kHz. Macintosh hi-fi valve power amplifiers powered the whole thing — a combination of the models 1000 and 2100, four altogether and summed to mono to increase their horsepower and drive the low end. “These were monsters,” says Heil, “but they were great-sounding monsters, as long as you didn’t overdrive them. They were audiophile hi-fi amplifiers. You could listen to records on the PA and they would sound great.” Heil estimated the wattage of the system that night at about 20,000W, which is astounding given that it was powered by hi-fi amps, but he had had the system as hot as 30,000W at one time.

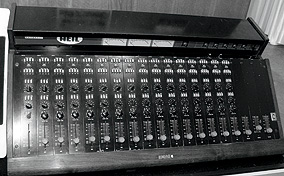

The console was equally ground-breaking. Heil had modified a Langevin studio recording console, adapting it for live work. As he has his entire career, Heil reached back into his amateur radio background to redesign the front end of this new console, using a balanced H-pad passive attenuator at the input stage of the console to allow adjustable gain on each channel input. “This was a studio console, so if you hit it with 120dB at a concert, you’d blow it out,” he explains. (A young student at the University of Illinois, Tomlinson Holman, introduced to Heil by a high school friend, did the rewiring. Holman would go on to create the THX theatre sound protocol.)

The wide, four-way frequency banding of the PA stacks would require speaker management, so Heil built an electronic crossover into the console itself, with a low-output cutoff at 250Hz, a low-mid from 250Hz to 800Hz, a high-mid crossover between 800Hz and 7kHz, and a fourth above that for the tweeters.

Back to the show

Heil had adapted a Langevin studio recording console for live work.

The Dead’s performance at the Fox that night had some other twists. With Owsley gone, Heil not only supplied the PA system, but the mixers as well. “My two roadies, Peter Kimble and John Lloyd, knew all the Dead songs — they were big fans,” says Heil. “So that night they moved the PA, set it up and mixed the show.”

The FOH position at the Fox Theatre was in the orchestra pit, in front of the stage. It was literally on top of the organ that Heil used to play at the venue. Not much perspective on the mix from that close up, but Heil reminds that, “In those days, the mix position used to be on the stage. Where you would put a monitor mix position today, back then they would be mixing the show from there.”

The monitor mix for the February 2nd show was also done from the FOH console, with a separate feed going into the Dead’s own wedges. With the huge PA stacks squatting on the stage and sharing the space with monitors, feedback was potentially a problem. “The monitor was always the big problem; they fed back all the time,” says Heil. “You would have a mic about three feet from the monitor and these guys on stage are playing louder and louder. It was feedback city.”

Heil was ready for it. In a technique once again culled from his radio work, he saw phase cancellation as the key to avoiding feedback in PA systems this powerful. If you look carefully at the pictures of the Dead’s show at the Fox, there are small second microphones taped beneath the main microphones. “We would run the microphones out of phase from the monitors, something that nobody had been doing yet,” he recalls. “Since they were out of phase with the microphones and the FOH system, anything that leaked in from the monitors would be cancelled out. As a result, we could get these things incredibly loud before they would feed back. That’s one of the things that Jerry Garcia really loved.”

Heil was also fond of bringing studio-quality microphones on stage. “I never cared for ‘stage’ mics like the Shure SM58, though so many of them were around that I was sometimes forced to use them,” he says. “The studio-type dynamic microphones, like all good studio and broadcast mics, have much better articulation. The sound system was like a huge hi-fi system, so it was a good match.” That was helped by what Heil calls the “magnificent acoustics” at the Fox Theatre, and the fact that he knew its nuances intimately, having played the organ there since 1955. (He was brought back to play it again at the reopening of the Fox in 1982, after it was saved from the wrecker’s ball and restored to its glory by community efforts.)

For all the madness of showing up at a gig with no sound system and no sound person, thousands of fans waiting to hear you, having no soundcheck, then taking the stage with a new PA system that must have looked rather intimidating, it says a lot for the Dead’s ability to take things in stride — or the quality of the pot they famously consumed in mass quantities. Either way, the concert went well.

“Everything happened so quickly that night,” Heil remembers, “and everyone was happy. Everyone’s always happy at a Dead show.” But he grows serious for a moment and still shakes his head at the thought of what went on that night. The culmination of the music industry dropping the innocent trappings of the hippie era and now calculatedly targeting a mass mainstream audience, as personified by the once musically meandering Grateful Dead on the cusp of releasing the tighter, radio-ready songs of the seminal Workingman’s Dead and American Beauty albums. And Bob Heil, who turned a lifelong fascination with ham radios and music into what would become the template for the modern concert touring sound system that was ready to roll the moment the moment arrived.

“We were pioneers, that’s for sure,” he says, a term not taken lightly in St. Louis, whose towering Gateway Arch monument recalls the time when the city was literally the last civilised stop on the way to the American West of the 19th century. “There were no books on this, no schematics,” he marvels. “We were freakin’ ham radio operators! And the bands were so obliging; they’d let us test anything out. They were just happy to see someone coming with more than a Shure Vocalmaster. And as a result the systems got better and better, and so did our understanding of how touring concert systems should be. The fans that night heard the Dead like the Dead had never been heard before. We made history!”

And the Grateful Dead concurred. They asked Heil to take himself, his crew and his sound system on the road with them, commencing immediately. They did, and the rest, as they say, is history.

The Who’s Next tour: the technology evolves

Bob Heil continued to improve his sound system. He built a second crossover out of the console, giving the system stereo capability, and used fibreglass instead of wood for low-frequency cabinets to reduce resonance. His next try at a live sound FOH mixing console would help to design the Sunn Coliseum, a Vocalmaster on steroids that gave large clubs, small theatres and local touring bands a tool that vastly expanded what music could sound like and how much space it could fill. He built more systems, both renting them out and selling them. What was now Heil Sound ventured with UK-based IES Systems, who had developed the Mavis mixer, which Heil describes as the first truly modern FOH desk with a modular circuitry design and external power supply. “It was an amazing console, though only four were ever made — they weighed 300lbs each!” he says. The two companies standardised key interfaces of their systems, such as speaker connectors, so they could use each other’s gear on opposite continents.

By then, Heil was onto his next big project, the Who’s Next tour. “The show with the Dead in St. Louis had changed live sound history and it changed my life,” says Heil. A story in music industry magazine Billboard reported that a small sound system purveyor in the Midwest that no one had ever heard of had suddenly snagged the Grateful Dead tour. Heil remembers getting a call from the management of the Who, who had been experiencing a bumpy start to their US tour. Heil says he brought a more refined and powerful version of his system along with his hand-wired Sunn console. “We did the Who’s Next tour for a year and a half, across the US, to Europe and back here again,” he says.

The experience created a bond between Heil and Who guitarist Pete Townshend, who called on Heil to make manifest the quadraphonic sound system he envisioned for the live tour on the heels of the release of the Quadrophenia LP. “It worked,” says Heil. “We set up two 15-channel Mavis consoles together, put speakers in four corners and we were able to fly Roger’s [Daltrey] voice around the room. When we did Madison Square Garden with Quadrophenia, the PA was enormous. I think we had on each side six to eight 15-inch speaker bins, six to eight radial horns, and about a dozen tweeters. We could get about 110dB to 115dB on that stage before feedback. And the Who loved it, man, because it was loud, and they loved loud.”

“It’s all about logistics now”

The Langevin FOH console and other ‘firsts’ that Bob Heil brought to the industry are now displayed in the Rock & Roll Hall of Fame in Cleveland, Ohio.

Bob Heil left the live sound business in 1982 and turned his talents to developing new systems, in particular microphones. He’s stayed up with developments over the intervening years, though he likes little of what he sees and hears these days.

“The quality of concert sound now is pretty bad,” he gripes. “You can’t understand the words and that’s because there are no horns in the systems anymore; it’s all just damn line arrays that are hung from the ceiling. If they do have horns, they’re tiny ones. We had 16 JBL 2482 [compression drivers] per side, with a four-inch throat the size of a paint can, driving 60-degree and 90-degree radial horns, as well as 32 ring tweeters — per side! You had mid-range and high end out the ass! Today, the mid-range is gone. Sound systems are now being designed to accomplish two things: create more low frequencies, and be able to be moved in and out of the hall faster. It’s all about logistics now.”

Where’d that Langevin desk go?

Heil Sound’s first FOH console went to the famous Mississippi River Festival in 1971, where it guided sound for musical entities ranging from the St. Louis Symphony to Iron Butterfly. Last year, it and a slew of Heil’s other live sound incunabula — including one of the IES Mavis mixers, one of the actual Heil fibreglass rear-channel speakers, the Serial No. 1 Heil Talk Box and many other ‘firsts’ Heil brought to the industry — went into a permanent display in the Rock & Roll Hall of Fame in Cleveland, Ohio.

Contacting Bob

Bob Heil, like most of the true greats of pro audio innovation, is always willing to take time to talk. We can’t give out his phone number or email, but he’s willing to let you contact him via another technology. He’s still available on the radio station licence granted him by the Federal Communications Commission in 1956: call sign K9EID.

Published in PM December 2008