Leading Guitar Tech: Michael Kaye – Tech That

Article from February 2009 PerformingMusician on Michael Kaye, guitar tech on recent Who tours

Leading guitar technician Michael Kaye chats to PM about the ins and outs of teching for a host of major stars, including the Who’s Pete Townshend, the E Street Band, Stephen Stills and Bon Jovi.

By Matt Frost

The last couple of decades have been something of a whirlwind for Michael Kaye, with Tracy Chapman, Cowboy Junkies, John Fogerty, Don Henley, Kenny G, Megadeth, Prince, Paul Simon, Stephen Stills, Brian Wilson and Warren Zevon being just some of the top acts that can stand up and say they’ve counted on his teching expertise at one time or another. Most recently, the year 2008 not only saw Michael attending to blockbuster tours by two of his regular rock & roll employers in Bruce Springsteen and the E Street Band and the Who, but he was also presented with a new (and now regular) teching gig with classic rock mainstays Bon Jovi. Michael always reveres the challenge of working with a new artiste, and the experience he garnered teching for the New Jersey rockers certainly didn’t disappoint.

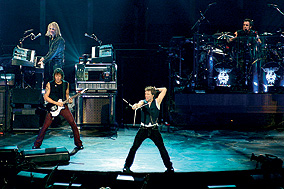

“Working with Bon Jovi was a really interesting experience,” says Michael, “especially in the summer when we were in the UK and Europe playing some of the big outdoor stadiums. It is such a large production with so much sound, moving video screens, a massive lighting system. Occasionally, when you’re working on a show, you lose the big picture because your job is to focus on a small part of that show. But a couple of times I was able to just stand back and get near a video monitor — when the camera pans across and you see the audience, it’s like ‘Wow’!”

Canada drive

Michael Kaye’s passion for all things guitar harks back to his early teen years growing up in his native Canada. Despite realising at an early point that he wasn’t perhaps cut out to make it as a stage star himself, it wasn’t long before he found other ways he could become involved in the intriguing world of rock & roll.

“When I was a schoolboy, at about the age of 13 or 14, I started getting interested in music,” explains Michael. “Music became our life — myself and my friends. We all tried having a go at playing music and it turned out that maybe I was the least talented, but I did have the strongest back! As my friends started to play more and more at events at school and that kind of thing, they always needed help with the gear. I was living in Ottawa, Canada, at the time and some of the bands that came through to play at my school were quite big, like Rush and Mahogany Rush with Frank Marino. I got on the school dance committee and worked as a humper, helping and trying to figure out why they were bringing all these boxes of stuff and what everything did. As I became an adult, I had friends in a band who had a record deal and we started doing shows around Eastern Canada. It just continued on from there. Bands would rise and then go away, and sometimes I could use that as a springboard to the next level!”

Indeed, Michael spent much of the 1980s working as a live sound engineer for a slew of different Canadian bands, including Teenage Head, Boys Brigade, Headpins and Doug And The Slugs — a period he refers to as his “training ground.” By the end of the decade, Michael moved across the border to the US, and it wasn’t long before he diversified into guitar teching. “After I moved to the US in the late ’80s, I found that I was able to get more work as a backline tech,” he says. “Playing a little guitar and knowing a little about guitars helped, and I did everything I could to learn more from that point on!”

Word of mouth

Since deciding to concentrate his efforts on the backline side of the tracks and more specifically guitar teching, Michael’s client base (and reputation) has grown so extensively that he can now virtually pick and choose which jobs he agrees to take under his wing. As Michael explains, once a tech or indeed any crew member begins to develop a good reputation, the power of word of mouth steps in and begins to take over.

“A friend of mine who was a production manager told me in the late ’80s that when it comes down to it there are really only a couple of hundred people that do what we do in the world at this level,” says Michael. “That’s true and we all kind of know each other. While you tend not to work with someone who does the same job you do, you do work with different sound guys, different lighting guys and different production managers. And when someone raises a question like, ‘Oh, we need someone to do such and such,’ they’ll say ‘Oh, I know so and so!’ It’s not often that a musician is asked, ‘Can you recommend someone?’ That happens occasionally, but it seems to happen less often. Usually, when a musician is hired onto a gig as the side man, the band will say, ‘Come play guitar with us and we’ve got a guy who’ll take care of your gear.’”

A case in point is how Michael ended up getting the Who gig. When it was decided that it would be beneficial to get Pete Townshend a second guitar tech, Alan Rogan, Townshend’s long-standing personal tech, knew exactly where to turn.

“Alan Rogan and I have been friends for some years,” says Michael. “I used to work for Stephen Stills with Crosby, Stills, Nash & Young, and Alan used to work for Graham Nash. We worked side by side on tours in 2001 and 2002. We’re friends and we know each other’s abilities, and I think that when it seemed it would be a good idea to get some extra help to look after the amps for the Who, Alan thought I had the strengths to complement what he was doing. And so far it seems to have worked out that way!”

Who’s responsibility

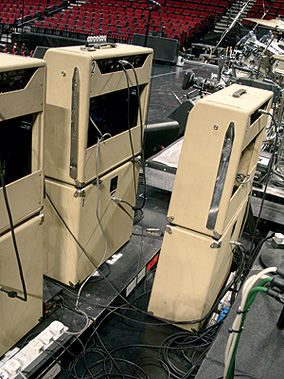

Pete Townshend uses two Fender Vibro-King amps with 2 x 12 extension cabinets underneath, and has an identical pair of stacks behind as spares.

Photos: Brian Kehew

Michael’s main gigs over the last couple of years have been his aforementioned stints with the Who, Stephen Stills, Bon Jovi and the E Street Band. And due to the differing approaches of the bands and personalities involved, each job offers up a healthy variance in Michael’s roles and responsibilities. He’s been working as a touring guitar tech for Stephen Stills since about 2000, covering solo tours as well as shows with Crosby, Stills & Nash, and Crosby, Stills, Nash & Young. For the E Street Band, who he’s been involved with since 2007, Michael techs for guitarist and vocalist Patti Scialfa, as well as violinist, guitarist and vocalist Soozie Tyrell. With Bon Jovi, Michael is responsible for the guitars and rigs of both Jon Bon Jovi and rhythm guitarist Bobby Bandiera. The Who gig is perhaps the most unusual as far as traditional guitar teching duties go, because of the fact that, as mentioned earlier, those duties are split between two guys.

“Alan Rogan has been working with Pete since the Rough Mix album [Pete’s collaboration with Ronnie Lane, released in 1977],” explains Michael. “Alan takes care of Pete’s guitars — the tuning, the guitar changes, the strings, the stretching and all that stuff. Then when the Who are not on tour, Alan will take care of anything Pete needs to do. For instance, on New Year’s Pete was going to do a little gig with Clapton, so Alan went out and did that because it was much more casual than a Who gig. My responsibility is to take care of Pete’s amps and pretty much everything involving the electronics, from the pickups — the magnetics and the piezo in the bridge — all the way through to the speakers.”

One of Michael’s key responsibilities is ensuring that Townshend is completely happy with his guitar tone, and if he isn’t, remedying the situation using the full extent of his knowledge and experience. Such remedying procedures can even take place mid-gig. “It’s knowing what’s going on and if things don’t seem to be going right. If you listen to Pete play, you can sometimes tell when he’s not comfortable with the situation,” says Michael. “Then it’s a matter of going out and seeing if you can find what doesn’t seem to be working and any kind of resolution.

“During the show, we have re-tubed and/or re-biased Pete’s amps on a number of occasions. During one of the last shows that we did at the Indig02 [December ’08], Pete was not quite sure about the response of his amps, so I did a little bias adjustment during the fourth song, ‘Fragments’, while he was playing. That way, both he and I could hear the change. It probably wasn’t obvious to the audience what was going on, but it allowed Pete to continue to play with confidence. A lot of the time with guitar players, they can appear to sound like them and make the sound that everyone’s used to hearing, no matter what amplifier they’re playing or which guitar they’re playing, but sometimes they have to work extra hard to get those sounds. You need to find an easy way to get those sounds, whether that’s in the setup of the instrument, the gauges of the strings, the amp settings or the valve bias. If you can figure out ways to make it easier for them, they will love you forever!”

Michael’s job with the Who can involve more maintenance and repair work than other teching gigs. Although these days Pete Townshend doesn’t trash his axes and smash his amps as he once did back in the ’60s, he does still give all his gear a sound pounding, which can mean a weighty dose of post-gig maintenance and teching TLC becomes something of a necessity.

“A Who gig can be very much full-on, with a lot of people paying attention to a lot of things to make sure it all goes right and nothing breaks,” explains Michael. “And Pete is very very expressive! He jumps three feet in the air and then comes down on the pedalboard, and his guitars are covered with blood more often than not! He really has a go at his guitars, so it takes some work to keep them going. Sometimes we get a Strat back and the pickup has been pushed through the pickguard, perhaps by the heel of his hand as he’s strumming, so you have to fix that and put it back where it needs to be. However, Pete is not all aggression; he can be very analytical and very precise when it comes to things like guitar setup and sound. I have seen Pete use an Allen wrench to adjust the bridge saddles of his guitar on stage during a show because something just didn’t feel right to him!”

Stills and E Street

Working with Stephen Stills offers up a different set of challenges for Michael, partly due to the fact that Stills can be using such a massive range of gear during the course of just a single show to cover his many different tones. “To run through Stephen Stills’ gear would take forever because we’ve used so many different things!” laughs Michael. “At times, we’ve had as many as six amps on stage, all used in different combinations! He’s used the Marshall 1962 reissue (which is also called the Bluesbreaker), the Marshall 1974X reissue, and there are almost always two 1959 Fender Vibrolux amps on stage. We’ve also used a 100W Silvertone, which was a cheap and cheerful amp sold in department stores in the US in the ’60s. For the Gretsch hollow-body guitar, we’ve used a 100W 610 amplifier. And we used a Marshall Triple Super Lead 602 for a while, which is a 60W 2 x 12 combo with a custom switching system. Effects-wise, there’s always a tremolo somewhere and an echo and a reverb.

“You try to get the right devices so Stephen can get the palette of sounds that he’s looking for. He will rarely say, ‘I want to use this piece of gear!’ He’ll say, ‘I want to have this kind of sound,’ so it’s up to the tech to figure out how to give him the sound that he’s looking for at the right time. We’re very fortunate that he has many of the guitars that he’s been playing since the 1960s, so there’s quite a number of very old and very valuable Fenders and Gibsons from the ’50s, as well as a lot of newer guitars. Often with Stephen, I could be travelling with maybe 30 guitars just for him and many of them would be very, very valuable!”

When teching for Patti Scalfia and Soozie Tyrell of the E Street Band, one of the biggest challenges can be getting the right Takamine acoustics ready in the right tuning at exactly the right time. Of course, this would not ordinarily present much of a problem for a guitar tech, but Mr Bruce Springsteen is a man who likes to keep everything spontaneous, including the set list!

“There is a set list written every night, but the set list is really just a guide,” says Michael. “Everyone has to try to figure out what song Bruce may decide to play next! They have a working repertoire of about 120 or 150 songs, so it’s pretty interesting sometimes when Bruce goes back at the end of the song to change guitars, because his tech, Kevin Buell, will have as many as five guitars there ready and you have to try to figure out which guitar Bruce is taking and which tuning it might be in. That will then give you an indication as to what everyone else may need! In the wings, once someone figures out what song it’s going to be, there’s a lot of calling out of song titles and running upstairs with guitars, getting ready for the start of that song. You just try to be as close to instinct as you can be. A lot of the time you’re running up with a guitar for a musician and they’re saying to you, ‘What song is it?’ and you’re going, ‘Well, I think it’s going to be this one!’

“One thing with band leaders is that if they’re going to call a song, it’s almost always one that they themselves are ready for, so it means that you’re already a half step behind, but over time you just figure out what guitars he’s using for which songs. For instance, if there is an open tuning. Often an open tuned guitar will only be used for one or two songs, so if I see a guitar go out and I know it’s in an open tuning, and I know, for example, that it’s used on the song ‘Working On The Highway’, I then know I need a guitar tuned in standard with a capo at the third fret. A lot of times, I’ll have a capo in my pocket so I can quickly put one on if I need to!”

Going spare

When teching for Bon Jovi, Michael is responsible for Jon Bon Jovi’s and Bobby Bandiera’s guitars and rigs.

Photo: Rosana Prada

When it comes to spares, there is commonality in Michael’s approach across all the high-calibre artistes he is currently teching for. Because of the scale of the shows he is involved in and the high budgets set aside to ensure everything runs as smoothly as possible, having spares for absolutely everything is pretty much a given, starting with the basics.

“Spares at this level are really important,” says Michael. “When you’re doing arena shows and stadium shows, or you’re doing a show where people are paying good money, there shouldn’t be any interruption in the show. You should have a spare ready to go at every level. At the most basic level, you’re going to have spare leads ready. Leads are the things that fail first in the course of a show. If you’re doing guitar changes, the leads are being pulled in and out about 30 times, and then the guitar player’s heel is going to be stomping on it and breaking the shielding in the wire. They get run over with road cases, they get kicked by people and they get things dropped on them. You’ve got to take care of your leads and have a spare lead ready to go at all times. I carry spares of every effect pedal and spare power supplies for the pedals, and always spare amps ready to go. It’s better to have all that stuff ready and tested in the afternoon, rather than not have it ready and then find you need it on what would be the most horrible day of your professional life!”

Wireless systems are something that Michael recommends you should always have backup for, due to the occasional unforeseen problem with frequencies and interference. “Many shows require that a player be wireless, because people are expected to move around as part of the show and they like that freedom,” he says. “I would always have a spare wireless ready to go and I’ll also have a long lead just in case there’s a problem with frequencies. Much of the wireless gear is manufactured in the US and sometimes they don’t fully understand what other wireless things may be happening in the UK or in Germany or elsewhere, so occasionally you run into funny little wireless problems or interference. Everyone is carrying a mobile phone and they’re radio transmitter/receivers, which can cause problems sometimes. Also, if you get a policeman or an ambulance man with a high-powered radio too close to the stage, things can stop working all of a sudden, so you have to have a spare plan for that!”

Tune and clean

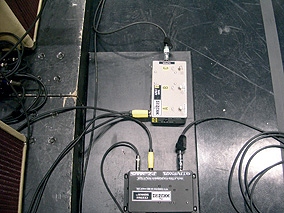

The signal from Pete’s pickups goes through a Pete Cornish splitter and then out to a Pete Cornish pedalboard, which has a compressor, overdrive and delay built in.

Photos: Brian Kehew

Michael’s approach to restringing does generally depend on the guitar player(s) he’s working for at the time. “Most often, guitar techs on the road will change strings in the hope that those fresher strings will lessen the chances of a string breaking on stage,” he says. “Occasionally, you’ll have a player who really prefers that you don’t change the strings. I’ve worked with a couple of people like that. I’ve worked with bass players who, for instance, might have a flat-wound sound and they do not want a bright, piano-like sound from the bass guitar, so they want old strings. I have worked for musicians where they go, ‘Oh, these strings are fine!’ but I’ve changed them anyway because I was really worried they’d break a string during the show. Again, that depends a lot on the player’s style. I’ve never seen Stephen Stills break a string on stage! Breaking strings actually can come down to the way the guitar is set up. If the guitar is super-easy to play, then you don’t have to hit things as hard to get the sound that you’re trying to get out of it!”

When it comes to actual tuners, it’s Peterson all the way for Michael, no matter what tour he’s on. “I got my first Peterson strobe tuner in 1980, I think, and I’ve stayed with Peterson tuners ever since,” he says. “A strobe tuner is much more accurate than any kind of LED device. It always seems that you’re looking for the in-between spots that the LED tuners don’t show. Sometimes you need the strings not to be tuned exactly mathematically to sound right. For instance, with most guitars that I tune, the low E string will be tuned a little bit flat and the second string, the B string, will also be tuned a little bit flat. That helps the chords sound sweeter. Sometimes a guitar that is tuned mathematically perfect will sound a little bit sour depending on what chords you’re playing!”

The cleaning products Michael uses will depend on who the player is and what instrument he’s playing. And it’s even important to take into account the amount and type of sweat a guy produces! “One of my pals, Mark Stewart, who plays with Paul Simon, has really corrosive sweat!” says Michael. “I let him play one of my Paul Reed Smith guitars on a tour and after the first week all the chrome plating was gone from the bridge and the bridge pickup. It was just from the sweat on his right hand. I needed to try really hard to get his sweat off the instrument as quickly as I could! A common approach I take to cleaning is to use a wax that’s made for automotive finish on cars. That just gives them a nice clean feel and it will also help protect from any moisture penetrating the instrument. If you do a nice cleaning job in the afternoon, then all you need to do come showtime is give them a quick wipe down and the guitar will look and play great.

The hardest thing of all is when guys play black guitars, because they show all the smudges and fingerprints, so I’ll often keep a polish cloth in my back pocket so I can just touch things up. I’ll have a light situated somewhere so that I can see the instrument and make sure that I’ve got all the stuff off it and all my fingerprints off it before I hand it to the musician. There’s no one particular product, because it really depends on the instrument. Some instruments respond better to some polishes than others and it also depends on the situation. My big work box has six or eight different types of polishes and cleaners. Actually, one of the cleaners that you can use for really bad stuff is petroleum-based lighter fluid. Like if there’s stickers on there or glue that you need to get off. It’ll help clean corrosion off of hardware, and if the screws are frozen it’ll often help. As long as no one’s standing beside you smoking, everything will be fine!”

Beck tech

While Michael will be more than happy touring through 2009 with some or all of his current ‘client base’ of Stephen Stills, the Who, Bon Jovi and the E Street Band, he does always savour getting new jobs with interesting guitarists he hasn’t had the joy of working with before. When we ask him who he would choose if he could hand-pick any other guitarist to tech for in the future, it doesn’t take him too long to fire back an answer. “Jeff Beck is amazing!” he says. “I’ve gone to see him play live a few times and I’d love to work for him, just to get a better understanding about what the heck he’s doing! When you tech for someone, you often get an understanding of exactly how they play and also why they play the way they do. Working for Pete Townshend has been absolutely fascinating, just like working for Paul Simon is fascinating. To be able to hear what they do and see what they do and see how they approach the same passage in completely different ways, that’s just amazing! Jeff Beck’s left hand is pretty tasty, but a lot of the magic is in his right hand. He’s got his fingers positioned round the vibrato bar, so he can raise or lower the pitch easily and accurately while he’s also able to manipulate his knobs and his pickup switch. There is a reason for everything he does.

Other than that, I would like to be able to work for one of the jazz greats to get an understanding of how they do it and why they do it. Luckily, some years ago I was able to be around George Benson a little bit. Everything that he did was fascinating, so to work for him or someone of that calibre like Pat Metheny, Al Di Meola or Larry Carlton one of those guys who approach the instrument from a different way than I’m used to!”

Pete Townshend’s rig for the Who

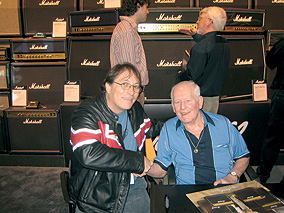

Michael with Jim Marshall at NAMM.

Photo: Shawn Welch

“Pete plays Fender Stratocasters, which have gold Lace Sensor pickups,” says Michael Kaye. “And they’ve got the Fender preamp on board, which gives a 25dB boost. They also have a Fishman Power Bridge, which gives a piezo signal [for Pete’s acoustic sounds]. The signals from the guitar go to a Pete Cornish splitter box, and the piezo then goes through to two DIs — a main and a spare. The main is a tube Demeter DI and the spare is a Fishman Platinum Pro DI. It’s not happened recently, but we have had problems in the past with valve DIs failing, and that’s why we have two of them in the signal path at all times, so if there’s a problem we can switch to the spare. The magnetic signal from the pickups goes through the Pete Cornish splitter and then out to a Pete Cornish pedalboard, which has a compressor, an overdrive and a delay in it. Then the signal goes back to the splitter box, which splits his signal to a number of amplifiers. Pete uses Fender Vibro-King amps with a 2 x 12 extension cabinet underneath, and if you look at the Who stage you’ll see four stacks up there. The front two stacks are used through the show, while the rear stacks are spares. We can switch them instantly by means of a footswitch, so everything’s there and everything’s on all the time!”

Published in PM February 2009

![“Pete [Townshend] is very expressive on stage! He jumps three feet in the air and then comes down on the pedalboard...” Photo: Retna](../images/articles/kaye/pm_guitartech_02_rtn_retnausapsd_t.jpg)