My Generation: Fifty Years With The Who

Sound on Sound interview with Bob Pridden during the Who’s The Who Hits 50 tour from March 2015

Published in SOS March 2015

Bob Pridden live sound engineer

By Matt Frost

We caught up with the man who’s spent nearly half a century in charge of live sound for one of the biggest bands in the world.

The Who pioneered the use of multitrack playback systems on stage, starting off with four-track tape machines, but now using a 24-track digital system.

There can’t be many — if any — crew members on the circuit who’ve been employed by the same band for five decades, but the Who’s live-sound guru Bob Pridden will soon reach that incredible yardstick. After taking up a job as the group’s roadie in 1966, it wasn’t long before Pridden began dedicating himself to injecting more “volume” and “clarity” into the Who’s live performances.

Throughout the late 1960s and ’70s, the Who were very much leading the way in terms of pioneering PA systems and improving on-stage sound for rock bands, and it was Bob Pridden who helped make their sonic ambitions a reality. Bob is also widely credited as the “inventor” of the monitor wedge, a development that so many bands, artists and sound engineers have long taken for granted.

We caught up with Bob, just hours before the Who played the Capital FM Arena in Nottingham, to talk about his life on the road and the highly innovative live-sound work he’s been spearheading for nearly half a century. In recent years — although he is still firmly in charge of the Who’s overall sound — Bob has been concentrating on Pete Townshend’s unique personal on-stage monitor setup and monitor mixes during the course of the band’s extensive global tours.

Smashing Time

Bob Pridden was just 21 when he joined the Who as a roadie in 1966. The young Londoner had already been cutting his backline teeth with mod troupe the Alan Bown Set for a couple of years, but the opportunity with the Who was too exciting to turn down. Bob’s early responsibilities, however, proved more than a tad tricky, to say the least.

“My role was basically setting the gear up every night, but then I also had to repair Pete’s guitars and the drum kit,” recalls Bob of those years when Pete Townshend’s guitars and Keith Moon’s drums were trashed at the end of almost every show they played. “After the first gig I ever did with them at the Locarno in Streatham [15th December, 1966], Roger [Daltrey] walked off stage and looked at me. I was looking at this pile of smashed equipment and knotted leads which looked like spaghetti, and his words as he walked past were, ‘Get all that fixed for the next gig!’ I just looked at him in amazement, you know... But I’ve always liked a challenge! It was quite a job to repair everything in those days. It was beg, borrow and steal to do gigs because there was always a shortage of money, which was down to the actual carnage with them on the road. I spent a lot of time repairing guitars with Pete. We used to use Cascamite glue on his old Strats, and actually I think I used to repair his Les Pauls too. I even repaired a Rickenbacker once, which was like putting matchwood back together. Then I’d be patching holes in Keith’s drumkit and re-putting stands together you know, the whole thing was like one huge Meccano set!”

Sound Decisions

As far as his fascination with live sound goes, Pridden actually dates this back to the days before he started working for the Alan Bown Set.

“I remember seeing a band many years ago, probably as early as ’62, and they were called Erkey Grant and the Earwigs,” explains Bob. “I remember they had a guy working the echo unit for them, which I think was really before its time and I think that probably planted a seed in my head... But when I started with the Who, I started to really get into it and I realised that one could make things better. It probably stemmed from the old days of the package tours when no one heard a thing. I just thought we could make things sound much better. But, also, the Who wanted to sound better all the time, so that was a big part of it as well. They were really the instigators. Pete used to mention things to me and we used to chat about it, and then we’d experiment with different pieces of equipment.”

During the 1960s and ’70s, the Who were renowned for being one of the loudest rock & roll bands on the planet. Was this always their intention?

“I wouldn’t go as far as to say they always wanted to be the loudest,” says Bob. “There’s no doubt about the fact that loud was part of the dynamics of the band, but they didn’t actually go out of their way to be the loudest band in the world. It was all just part of their dynamics. Being loud suited their music because there was only four of them but we believed it was good to have volume with clarity, and that’s what we went for.”

PA Evolution

In the early years of Bob Pridden’s tenure with the Who, the PA system the band used was pretty straightforward, but it did work for the smaller-sized venues where they were performing.

“Equipment was very archaic in those days so we used to change things around a lot,” explains Pridden. “We used to use four Marshall 8x10s. The two outside ones had the vocals and the two inside ones had just the drums, because the band were so loud that you didn’t need a PA for the bass and guitar. They were only playing 1000-seater halls and you could hear the guitar and bass without a PA. Then things evolved from there, obviously. When we were in Scandinavia [mid-1968], we found a PA called an Ackuset, which we started using with the Marshall system. The Hollies used to have one too and we thought if they were using it, it must be good, so we got one and that had an echo built in. That’s when all that started, and that echo unit was a great little unit, actually. After that, I started to get into [Watkins and Maestro] Copicats and Echoplexes, and Binsons. There were all kinds of echo units that I used to use on Pete’s guitars and on vocals.”

In 1969, the Who moved over to WEM [Watkins Electric Music] PA systems, comprising varying numbers of WEM speaker columns and a WEM Audiomaster mixing desk (you can read all about the history of WEM and its founder Charlie Watkins in last month’s issue of SOS, or online at https://sosm.ag/feb15-watkins). But, as Bob Pridden explained, with the group gigging at increasingly larger venues, including huge open-air festivals such as the 1969 and 1970 Isle Of Wight events, the WEM system no longer fulfilled the Who’s ambitious sonic requirements.

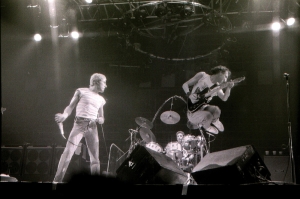

The front-of-house mixing setup for the Who’s 1971 US tour included two Bob Heil-modified Sunn consoles. [Note: Image is of West, Bruce & Lange, in April 1972 at the Kiel Opera House, St. Louis, Illinois.]

“The WEM system just outgrew itself,” says Bob. “We ended up with about two or three thousand Watts of WEM stuff which we used at the Isle Of Wight festival, and then we bumped that up with Pink Floyd’s WEM system to make it even bigger but, really, with that stuff, for every 1000 Watts, you only get about a couple of extra dB, so it really didn’t cover big gigs like that. In those days everyone suffered with that problem. The second Isle Of Wight [1970] was just so big and that’s when you needed to get something with horns in it to project the sound. The WEM system was great at smaller venues because it was a big hi-fi system, but when you started playing to crowds of, like, 50,000, 100,000 or whatever, it just didn’t work.”

Here Comes The Sunn

Funnily enough, Bob Pridden had actually glimpsed a way forward for the Who’s live sound a few years prior to the Isle Of Wight performances. It was during an early tour of the USA: “We were doing the Murray The K show in New York in 1967 or ’68, I think it was,” explains Pridden. “A band called the Young Rascals brought their own PA in and they had horns and bass bins. I looked at it and thought, ‘This is the way forward!’ That was really one of the first times that I saw a system with horns and Altec’s the Voice of the Theatre system. That’s what they had for the sound in cinemas. They were pretty basic, with Altec mixers, but the idea was great and they really threw the sound.”

During the band’s 1971 US tour, the Who started playing through a mammoth new PA system built by Sunn and US gear guru Bob Heil. “Bob Heil and Sunn built that together and especially for us,” says Bob. “That happened just by Bob Heil being introduced to me by someone, and then we all got together and they built a JBL system, but it was all enclosed in Sunn cabinets. It had two-way crossovers and horns with 2440 drivers — probably four horns a side and eight bass bins a side — and 15-inch loaded cabinets. What I hadn’t liked about the JBL Altec system was that the sound was very harsh, but this one was really great. The first time we used that system in America, it was sensational! It was really the first time people had heard decent stuff with horns! We brought it back to England with us and we played the Oval cricket ground in South London [18th September 1971, other acts included the Faces and Mott The Hoople] and used it there. Of course, everyone else used another system but, when it was our turn, we switched ours on and it was just unbelievable! Later on, they came out with a Sunn mixer, which took the place of the old WEM Audiomaster. I can’t remember how many channels they had but we had two of them and we had sends for the echo and we used to mix the monitors from there as well.”

Next came some of Bob Pridden’s favourite ever Who consoles, built by British-based manufacturer IES (International Entertainers Services), who the band had begun using for all their PA needs. The company’s head honcho Dave Hartstone came up with the innovative (albeit heavy-duty!) console.

“IES brought out their own mixer called a Mavis,” explains Pridden. “It was a fantastic mixer but it weighed a ton! It was really just like a Neve — not as good, but along those lines. We bought one of the first ones they built and used that and we ended up with two in the end, which we put together, and we used them for years. They were really good mixers. And that was the first step into real front-of-house desks. We used a Mavis mixer when we made the album Quadrophenia [1973], for mixing the cans in the studio so they could have their own four different mixes. We had various other mixers built for us in the old days when they first came out — modular systems — but they were just not really cutting the mustard because they were still in their early stages. You know, I remember one mixer we had made for us and it was a quadrophonic mixer and it had a three-way switch so you could switch each of the four channels to left, right or centre. They were on electric light switches so that’s how antiquated it all was! It worked quite well but it wasn’t really roadworthy. We ended up selling it to the Average White Band in the end. Later, we went to Martin Audio systems and, at first, we used a Neve as a sidecar with a Mavis and from there we went to using Midas, which I’m still using today.”

On The Wedge

Bob Pridden estimates that it was back in 1969 — around the same time the Who had just started using WEM PA gear — that he and the band first began experimenting with on-stage monitors.

“We just started thinking, ‘How can we hear ourselves?’” says Bob. “And then I got an amp with a volume control and turned two speakers with the full mix inwards across the stage, like two side fills. Then I just took it down a bit so it didn’t feed back, and that really was the beginning of monitors.”

Bob is famously credited with playing a key role in coming up with the design for wedge floor monitors. How did those first wedges come into fruition and how did they develop from there?

“Oh crikey, I don’t know how we came up with them!” he laughs. “They were really antique at the time though! They looked like rabbit hutches and that’s what I used to call them. They were just these boxes on the stage with wire grilles. They look a bit smarter now but they haven’t changed that much. They basically have better speakers now, maybe better horns, but they haven’t changed that much really. We didn’t use wedges with Bob Heil or Dave Hartstone. We only used side fills and that’s why everyone’s a little bit deaf, I think, because we had two lots of four, two in each corner. That setup gives you a great sound but we can’t use them anymore. They’re too loud, but it was undoubtedly the best sound we’ve ever had on stage — it was just there! The first wedges we had were made by a company called Tasco. The horn was in another box you clipped on the top but they were always falling off and what have you. Then, of course, they got more and more developed and we started using a company in America called Showco. They were the first really great monitors. We bought some from them and used them all around the world. They were absolutely great — huge wedges — but the sound was superb! I think we had about eight of them and then, from there, we went to using Clair Brothers and their wedges. I loved their AM12s. They were great wedges but then dB Technologies came out with their wedges and I thought ‘Look no more!’ The dB Tech system had been so well designed. One of the things that I noticed in general was that you could hear the bass coming back from the PA, but dB Tech cancelled that out completely and it really cleared up the sound on stage.”

Monitor Thoughts

Although he is still in charge of the Who’s overall sound on the The Who Hits 50 tour [2014–15], Bob Pridden’s main responsibility is Pete Townshend’s monitor setup and mixes during the shows. Chief monitor engineer Simon Higgs mixes the monitors for all the other seven current Who band members, with additional help from Trevor Waite. Everyone is now using in-ear monitors aside from Pete’s brother Simon Townshend (guitars and vocals), who has one in-ear and one wedge, and Pete himself, who has four speakers set up around his spot on stage. Bob is not a big fan of in-ears.

“Pete is only on speakers and has only ever been on speakers,” explains Pridden. “We’re both from that world because we like to hear that sort of thing. It’s more natural. I think it’s got to the stage now where it’s almost all in-ear systems everywhere. In-ears do work really, really well but I still like to hear the sound on stage. They’re very, very good for singers — there’s no doubt about it — but when you hear a band with all their in-ear systems and you’re standing on stage, you don’t hear anything. I like to hear the sound of the band on stage with the vocals on stage. You can use mics to get the ambience but you don’t get that feel of the actual sound working itself. In-ears do work for people, obviously, and it’s the way forward for a lot of them, but it’s not my way. For me, you lose a lot of the dynamics of the music.”

So how are Pete Townshend’s speakers divided as far as Bob’s monitor mixes go? “There’s a left and right, a centre speaker for the vocals and a far left speaker for electric and acoustic guitar,” says Bob. “I split the drums into the left-hand side speaker with the bass and keyboards and then Simon’s guitar in the right-hand side speaker. The vocals are spread. There are also a few tube traps and they suck up all the horrible lower-bass frequencies that are going around and help to give Pete a better sound on the stage because, instead of getting a bit mushy, it really tightens things up. Pete can then move away from the monitors and, for example, get more drums if he wants. Rather than having everything blasting out at you, you have more control and the sounds are enhanced. We’ve always used something along those lines for him but this time it’s got even more sophisticated. It’s all analogue. There’s no computer board. We use a DiGiCo board for the rest of the monitors and there can be up to a hundred channels, but I’m an analogue man and Pete likes analogue sound, so the Midas XL3 works for us.”

When he considers general recent monitoring trends and the complexities and endless options that can arise, part of Bob Pridden almost wishes he hadn’t begun experimenting with the concept at all back in the late 1960s.

“I’ve got to be honest with you, I started this whole monitor nightmare off with several other people at the beginning and, at the time, it was a good idea,” he sighs. “But I’m stuck with it now because of that, and a lot of other people have been stuck with it, and I feel sorry for all those poor people! At the end of the day, the monitors are a monster because they spoil everyone. Now what you have is that, however many people are in the band, they will all want different mixes. Half the time, when you’re a monitor engineer, you can’t keep everyone in a band happy because they’re never happy. That’s just the nature of the beast and it can be a very, very soul-destroying thing for the engineer. I just say, ‘concentrate on the music for god’s sake!’ It’s all got so complicated and everyone wants more and more. Monitor setups have got ridiculous. I mean, I’ve got a recording studio behind me up there on the side of the stage! As I’ve got older, I’ve realised that I just can’t really live with that anymore. I just hear some of the mixes people want and think, ‘how can you listen to that?’”

As far as managing the overall sound goes, Pridden takes the majority of all the important decisions in tandem with Pete Townshend and Roger Daltrey. “I decide on the PA that we use and I usually decide who we’re going to use as Front Of House along with Pete and Roger,” explains Pridden. “Obviously, whatever they’re comfortable with, I’m comfortable with. I’ll then decide what changes need to be made, if there are any. We record every gig too and that’s quite a lot of work. I just make sure everything runs smoothly and we’ve got a backup. If there are any problems, Pete and Roger will come to me but, touch wood, this tour’s been going pretty well actually.”

Studio Highlights

As well as spending the majority of the past 48 years on the road with the Who, Bob Pridden has also spent a healthy amount of time frequenting various recording studios, working with his main employers and other leading acts. In his early years with the Who, Bob played the role of casual observer during recording sessions: “I used to take great interest in watching the engineers, especially Glyn Johns,” he tells us. “Obviously, a lot of influence came from watching these people and those experiences helped me to evolve into working in studios by watching the way they miked things and everything.”

Before we let Bob head off to make some final stage preparations for the Who’s gig in Nottingham, we just had time for one final question. What are some of his favourite studio highlights? “That is a difficult one because being in the studio is always a highlight!” he laughs. “But no, it’s been great and I’ve worked with lots of great people. Obviously, I’ve always had a good time recording with the Who and have been more and more involved as time’s gone on. I was involved with the production on ‘Endless Wire’ [2006] and also on some of the earlier stuff as well. I’ve also mixed a lot of the live recordings too. Two projects I did really enjoy were mixing Tommy and Quadrophenia to 5.1. Then, over several years, I did a lot of production work in the studio with a band called Cast, and that was really a highlight and was great fun.”

So what’s next? “Actually, I’m just about to go into the studio to mix the Who Live At Shea Stadium from 1982 and that should be great fun too. I’m really looking forward to it.”

It’s Playback Time!

Back in the early 1970s, the Who were not only one of the globe’s most pioneering groups in terms of PA size, quality of live sound and the development of on-stage monitor systems, they were also using live tape playbacks before most other rock & roll bands on the circuit. Yet again, Bob Pridden was central to making this happen, while he was also the man with his finger on the buttons!

The Who pioneered the use of multitrack playback systems on stage, starting off with four-track tape machines, but now using a 24-track digital system.

“We started off using tape playback probably around the time of Who’s Next [1971], but it was very archaic,” remembers Bob. “We were one of the first bands to do it although I think Pink Floyd started to do it not so long after us. We started off using Revoxes but then we decided we wanted to split the tracks up so we got some Sony quarter-inch four-track recorders and used those for a while. But we started getting a few problems and I felt we needed a bit more so we got half-inch four-track Scullys on stage, which were fantastic! The thing is we only had one in those days and, of course, when they were doing a set, all of the backing tracks were on one reel and so if they changed the set around, I had to spool back and spool forward — that could be a nightmare! By the ’89 tour, I just got so fed up with it that I got three TEAC four-tracks and I got a switcher box made. Each track was on its own reel so I could have four different songs up at a time and switch between them if they changed their minds, or change one while another one was running. Later, we changed to Fostex eight-tracks.

Now we’re using 24 tracks, but it’s not all for audio playbacks — it’s also for the cue systems and what have you for everyone who’s using in-ears.”