Pete’s Gear: Rickenbacker Guitars

Pete Townshend and Rickenbacker guitars

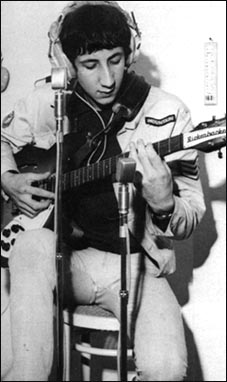

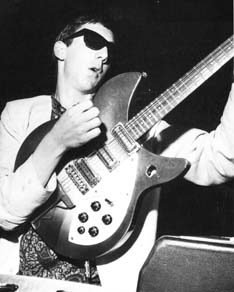

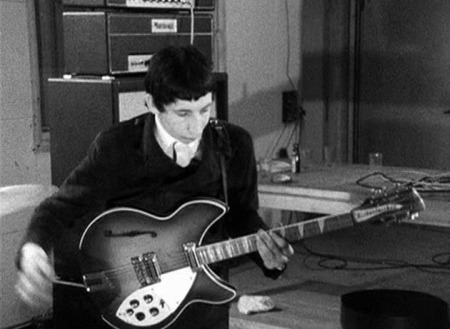

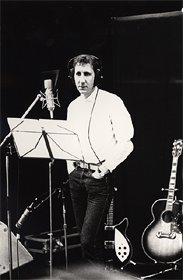

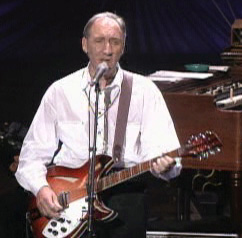

Recording with a 1998.

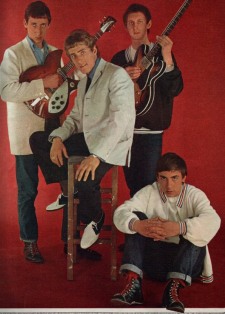

Early in Pete’s career, Rickenbackers were the guitars to have. The British Invasion was led using Rickenbackers (with the Beatles and, in America, the Byrds, being probably the most renowned users of Ricks).

Not only were Ricks his first persistent stage guitar, they helped define the early Who recordings, from I Can’t Explain, Anyway, Anyhow, Anywhere (both likely using the 1964 360/12 “Export” pictured below) and My Generation (a Rose, Morris Co., LTD, 1998), into the second LP.

Pete used (and abused) various Rickenbacker models, which were imported by the Rose, Morris Co., LTD, which still operates as a music store in London (rosemorris.com), Shaftesbury Ave. These models were export variations on their American counterparts.

First Rickenbacker

His first purchase of a Rickenbacker was likely a Rose, Morris Co., LTD, 1998 model in early 1964, either directly from Rose Morris or from Jim Marshall’s music shop in Uxbridge Road, Hanwell, West London. This 1998 was fitted — either when purchased or later by Pete — with a Gibson ES-175 “zig-zag” tailpiece. His second was a 360/12 “Export,” from Jim Marshall’s, for £169, both of which are likely pictured below in the 1964-era High Numbers photos.

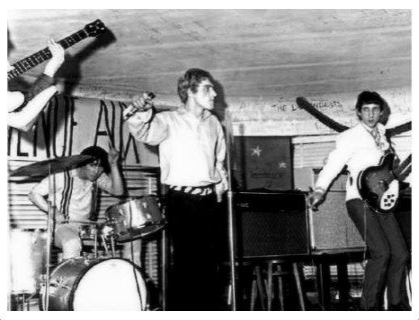

Chris Downing (guitarist, The Macabre), in Eyewitness The Who regarding The High Numbers appearance at the Railway Hotel, Harrow & Wealdstone, in July 1964:

This was the first time I actually saw them. Pete had the 360 Rickenbacker then, which cost £169 out of Jim Marshall’s shop. It was one of the first five that came into the UK, and I had one of them as well. He liked it because it had a very mod look, and it was great for playing chords. That big power-chord sound he got wasn’t just his amps, it was partly that he used really thick strings.

The 1998 was pictured in the infamous “Maximum R&B” Marquee Club poster. This guitar was the first (of many) to turn to smithereens, when its neck snapped off against the ceiling of the Railway Hotel, Harrow and Wealdstone, in September 1964 (according to Eyewitness The Who, 8 September):

“I started to knock the guitar about a lot, hitting it on the amps to get banging noises and things like that and it had started to crack. It banged against the ceiling and smashed hole in the plaster and the guitar head actually poked through the ceiling plaster. When I brought it out the top of the neck was left behind. I couldn’t believe what had happened. There were a couple of people from art school I knew at the front of the stage and they were laughing their heads off. One of them was literally rolling about on the floor laughing and his girlfriend was kind of looking at me smirking, you know, going ‘flash cunt and all that’. So I just got really angry and got what was left of the guitar and smashed it to smithereens. About a month earlier I’d managed to scrape together enough for a 12-string Rickenbacker, which I only used on two or three numbers. It was lying at the side of the stage so I just picked it up, plugged it in and gave them a sort of look and carried on playing, as if I’d meant to do it.

“The next day I was miserable about having lost my guitar. Roger said, ‘You shouldn’t have smashed it up, I could have got it repaired for you.’ Anyway, I’d obliterated it.”

Pete claims he smashed only about eight Rickenbackers total. He would repair destroyed ones for further stage use and eventually, began using another, more solid-bodied guitar that could withstand the smash-up routine and be repairable.

Pete continued to use Rickenbackers on stage and in the studio through 1965 and 1966, with a temporary switch in December 1965–January 1966 to a semi-hollow Grimshaw Short Scale guitar, fitted with a Rickenbacker truss-rod cover. Though because of the Rickenbacker’s relative fragility, he would begin to use a Fender Telecaster or Stratocaster or other more solid-body — and repairable — guitar for the smash-up routine.

By late 1966, he was still using a new-style Mapleglo 360/12 model (previously owned by Graham Nash), but had transitioned to primarily Fender Stratocasters, with other miscellaneous guitars, such as semi-hollow Gibson ES-335s, Gibson ES-345 Stereos and Gibson ES-355s, as well as brief periods with a Gibson SG EDS-1275 doubleneck and Fender Jazzmaster. These guitar would fill the time until his next “definitive” stage guitar, the Gibson SG Special in late 1968.

Later use of Rickenbackers

Pete would return to Rickenbackers later in his career, in the studio: using a 1964 330S/12 double-bound Fireglo (painted black) 12-string, with tapewound Rickenbacker strings, extensively on the Face Dances LP in 1980–81; and later, on Psychoderelict in 1993, using various old, reissue or current models, including the signature Pete Townshend Limited Edition 1997PT.

Plus, they reappeared in the stage rig, first, in at least once in 1980 (at Hallenstadion, in Zürich, Switzerland, 28 March, 1980), with a Jetglo 12-string; then on the 1989 tour (Fireglo 1993 reissue [or 330/12] and reissue 360/12V64 12-strings) and the 1993 Psychoderelict tour (likely Fireglo 360/12V64 12-strings).

Signature model: 1987

In 1987, Rickenbacker released a Pete Townshend Limited Edition Rickenbacker model 1997PT guitar, based on the the six-string Rose Morris Co., LTD, Rickenbacker 1998 model Pete used extensively in 1965 and 1966. This reissue was limited to 250 guitars.

1993 Plus

In 2015, Rickenbacker announced a Rickenbacker’s model 1993Plus 12-string. Though not a signature item, Pete was involved in its development.

Selected quotes from Pete Townshend

All quotes and references are copyright their original owners and are included for reference only.

Guitar World, October 1994:

The toggle switch thing was literally to make the guitar sound like a machine gun when it was feeding back. And when I bought my first Rickenbacker, I packed it with paper and found I could actually produce feedback on select harmonics, which was quite extraordinary. You can hear it briefly on “Anyway, Anyhow, Anywhere.” And I could reproduce it live. I could actually do that by moving the guitar in relationship to the speakers and get harmonics. That was extraordinary to me, to be able to reproduce that live. And as long as I kept that guitar — which was briefly, unfortunately — I could do it. It was a stunning example of how we were able to reproduce very difficult studio recordings live.

From April 1980 issue of Sound International article, courtesy Joe G’s site.

- How did you happen to choose a Rickenbacker?

PT: I liked the look of it, I think because The Beatles were using them. They picked theirs up in Germany, they were real German ones. I stayed with Rickenbackers for a long time and then I started to use Fenders.

Melody Maker, August 1965

The real wrecker of the group, guitarist Peter Townshend, owns nine guitars, all on HP. Five of them cost £170 each, four of which are already smashed to bits. He also has an imported 12-string guitar, cost £50 [likely £350–Whotabs]. total is £1,200 in guitars. That’s not all. Mr Townshend claims to have every amplifier and speaker he has ever possessed — he uses them for home recording. They are three amps at £150 each; two stereo amps at £80 each; four 100-watt amps which cost £160 each; five £80 speakers, and three 4 by 12’s which are £160 each. Peter records many singles for the group and other artistes in his own studio which cost £1,000 to set up. He gets through eight sets of strings a month at one guinea each — and 100 picks a month at 2s each. He buys four or five guitar and amp leads a month for the group and himself, costing about £10. The group have a £50 per month repair bill to their gear. Clothes-wise, Pete spends about £20 a week on a jacket.

The History of Rickenbacker Guitars, by Richard R. Smith, 1988, comments by Pete.

“I used Ricks on stage until 1967. In the studio I still use them today. I have a couple of 12 strings and 6 strings, 360 types, not special models. They sound clear, bright, and play very well. I use tape wound Rickenbacker strings on the 12 strings. It’s important.”

Rickenbacker, by Richard R. Smith, 1987, comments by Pete

“The delicate body shape, the lightness of the woodwork, the carefully constructed craftsmanlike neck all contribute to a guitar that is utterly different in every way from all other makes. I often feel that Rickenbackers are like violins rather than guitars, modern and delicate.”

- How many Rickenbackers did you break on stage?

I broke about 8. This was in the days these guitars cost around £250 apiece. … I was perversely proud of the fact that I was smashing up the most expensive guitar in London shops during the early ’60s when I still didn’t own a car or an apartment.

Guitar World, June 1994

“The strings are closely spaced on a narrow neck,” Pete explained to Rickenbacker historian Richard R. Smith. “The fingerboard is lightweight but superbly balanced. This suited my chordal style, and I invented several new chord shapes using that neck which have since become standard rock shapes. What falls under the fingers on a Rick might dislocate your hand on an old acoustic Martin. The lightweight neck allowed me to produce vibrato techniques by moving the neck backwards and forwards. This became another characteristic of my style. The weak points of the [Rickenbacker] guitars were that the necks would literally break off in my hand if I went too far.”

Guitar, December 1973

When I first got amplified with big speakers, I used to have them at waist level. I could never work out why most people played with them on the floor. I wanted them belting in my ear-hole. So I used to put mine on a great stand so the speaker was actually firing into the guitar pick-up dead level. Feedback started by accident and I started to use it. Simple as that. The more I used it, the better I got.

On a Rickenbacker I can still play a tune on feedback — through breaking harmonics and pickup up the partials and feedback — without actually touching the strings, just depending on what angle you turn to.

- How does it work?

You’re actually shortening the feedback vibration, the actual sort of path. The distance you are from the speaker affects what partial of the particular note that’s feeding back is going to stand out most. Like it might be the root note, or the first or second partial — you even get sevenths and quarter notes. You can’t get some of them any other way: there are only seven usual partials: you can get them on those — what do you call them? — wind things, wind lutes, I think they’re called. The wind blows across about twenty strings that are all tuned to A, and you get these strange haunting partials thrown up, just from the note A. On the guitar, with feedback, you can get all these, and even things like the leading note. That’s a pretty difficult harmonic to get, but you can get it easily with feedback.

From Before I Get Old

At the Oldfield, Townshend sometimes placed his amp on an unused piano at the back of the stage. When he switched to Rickenbacker guitars in late 1963, he began placing the amp at the same height as the guitar’s single-coil pickup, causing electroacoustic feedback.

“The Yardbirds, funnily enough, were the reason I hit upon it,” Townshend told Paul Nelson in 1968. “When I was at school, I lived with this guy who used to go and see Eric Clapton. And he would come back saying, ‘Look, you’ve got to do this! Eric Clapton does this great thing where he goes ba-ba-ba-bam on the guitar for hours and hours and everyone goes crazy and lights flash on and off and it’s great, it’s great.’ So I used to go ba-ba-ba-bam and attempt to do this from what I’d heard from him. Luckily enough, the influence, which could have been very obvious and direct if I’d actually gone to see Clapton was very effective coming secondhand.

“I used to play at this place where I put my amp on the piano, so the speaker was right opposite my guitar. One day, I was hitting this note and I was going ba-ba-bam and the amplifier was going u-ur-ur-ur on its own. I said to myself, ‘That’s fun. I’ll fool around with that.’ And I started to pretend I was an airplane. Everyone went completely crazy.

“I started to use it, I started to control it. I regulated the guitar so that the middle pickup was preamped on the inside with a battery and raised right onto the strings so that it would feed back as soon as I switched it on. And I could control it and go through all kinds of things.”

Entwistle and Townshend soon after started stacking their amplifiers, with their huge four-by-twelve speaker cabinets. (Townshend at first used to place his amp on a chair to locate the feedback.) “An electric guitar is really a guitar and a microphone,” said Roger. “Pete used the microphone part instead of the fretboard. He wasn’t interested in the technical qualities — he’d use it in a completely different way than [Jeff] Beck or [Jimi] Hendrix. He’d just bang it.”

Guitar For the Practicing Musician, August 1996

- How did it feel then to smash your first guitar?

Well, it was equally dumb, in a way. I was in the middle of an experimental session of trying to excite different noises from the guitar by feedback, by banging it, putting it up against the microphone, putting the feedback into the PA column. Then I discovered that even if you held it up close to a fluorescent lamp, things would happen. All those things I was doing, but lots of banging and physical stuff as well. And posing, kind of mod posing — they used to call me “the Birdman” [gets up and lurches about with arms flapping]. Then I was in this club and I was banging on the ceiling playing with my Rickenbacker, and I didn’t realize how flimsy they were. You know, the Rickenbacker company has always hated me saying this, but the fact is that their guitars are very, very delicate. I used to say they were just flimsy, but they’re delicately built instruments and there was not a lot of wood in the thinnest part that flares out into the headstock — it was very, very narrow. So I banged it against this low ceiling and it fell off. I just went bam! and it fell off. A couple of people sitting in the front row looked like they were thinking “That’s what he gets for being a showoff.” But I thought, “Right, I’ve been here before.” I suppose I saw my grandmother’s face or something, and if I’d really been in the right frame of mind, I probably would have smashed the guitar right over the guy’s head in the front row and maybe killed him, which would have been an interesting departure for my career. Instead, I just decided to just finish it off in a kind of a very carefully considered act of artistic destruction, and I smashed it up. I realized then that there was this incredible excitement in the audience. And John was as cool as ever, because he’d seen me do this before with the amplifier, thinking, “Oh, he’s doing it again.” Keith was kind of like, “What the heck’s he doing? He’s gone completely insane.” And then I picked up my other guitar, which was a 12-string, and finished up the show. I didn’t mention it, I didn’t pick up the pieces, I didn’t touch it. That was it, really.

In today’s terms, it was a $3000 guitar, and we were making pennies. But once I’d done it, the club was pretty packed the following week. You couldn’t have gotten another individual through the door. I started to think I couldn’t smash up my 12-string — I remember it cost 450 pounds sterling, which was a lot of money in 1963, around a thousand dollars. I’ve now discovered that in that year they made, like, six. So they were rare guitars, and they were precious guitars, they sounded absolutely wonderful with the double Fender rig. Anyway, that week, Keith knocked over his drum kit, and then that’s what we became famous for. I repaired other guitars to smash; I’d repair them myself. I’m not a luthier by any stretch of the imagination, but I could make a guitar. Roger made his own guitar, John has made his own basses. And we certainly made our own amplifier cabinets in the early years. I’ve repaired acoustic guitars and electric guitars. A lot of them have been smashed to smithereens many times between concerts. When we were first playing New York, we were playing five shows a day at the RKO, and I ended up with one guitar a day, so I had to repair it every time.

Jim Marshall: The Father of Loud, 2004

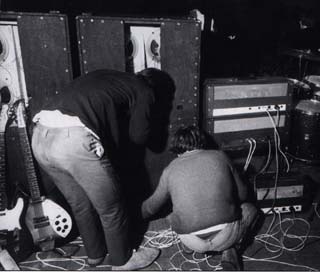

“…When Pete started breaking the guitar, his dad and I thought, ‘The kid has gone stark raving mad.’ But Pete brought the first two Rickenbackers into me and he said, ‘Can you do anything with these? The idea is, I want them to appear to be the ones I’m using.’ What he used to do was, he’d be playing and then at the right time he’d quickly switch to one of the guitars I’d repaired; I had glued it together so it looked to be perfectly normal. And he’d break it again. He was not as stupid as everyone said!”

Excerpt from The Soul of Tone: Celebrating 60 Years of Fender Amps interview with Alan Rogan

“Pete has used Fender amps off and on for 40 years. [Re: the My Generation album:] I said, ‘Oh, Pete, it sounds fantastic,’ and he told me exactly what he used on it: two Rickenbackers — a 6-string and a 12-string — and a blonde Bassman head with a Marshall 4×12 cab. That was the sound on that album, from 1965.”

Excerpt from The Guitar Magazine interview, July 1993

On the recording of Psychoderelict:

… ‘the new 12-strings are probably better than the old ones. I’ve gone back to a real love affair with Rickenbackers’ …

Photo Gallery

1998

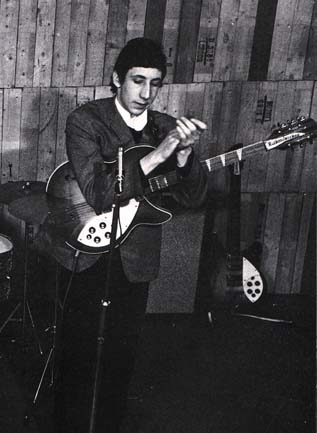

1964 360/12 “Export” 12-string

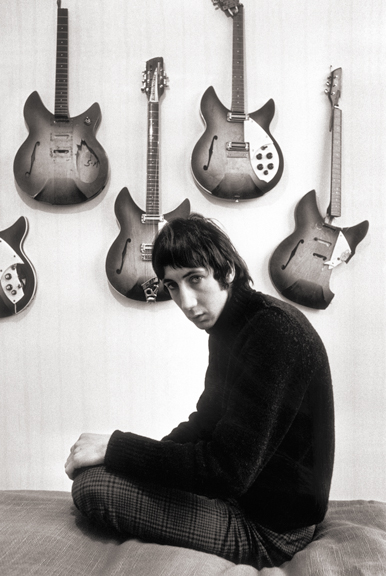

Colin Jones’ famous photo from The Observer in 1966: Pete in his Belgravia flat. From left to right, 360/12 Export, 1998, a relatively unharmed 1993, with intact “R” tailpiece, 1993, 1998.

Pete, in Rickenbacker, by Richard Smith:

The guitars on the wall in the famous picture by Colin Jones of the Observer were all taken by a roadie to be repaired by his father. I never saw them again.

12 November 1966, promotional appearance at the Duke of York’s Barracks, Kings Road, Chelsea. 1965 or 1966 360/12 Mapleglo (New Style). A Rose, Morris Co., LTD, 1998 lies in wait. Amps are Marshall JTM45 100 100w Tremolo head (top), and 1967 Marshall Major (“Pig”) 200w head (bottom), with Marshall 8×12 cabinet.

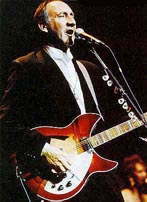

Restringing a 1997.

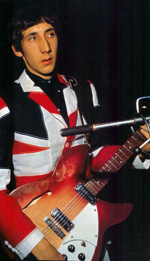

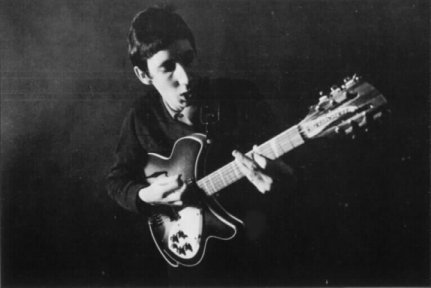

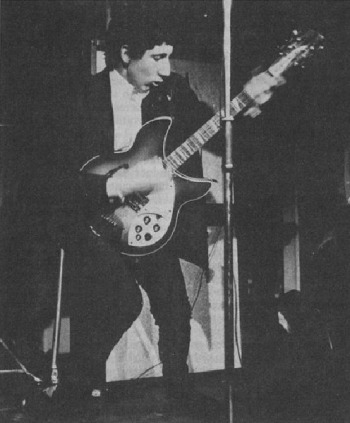

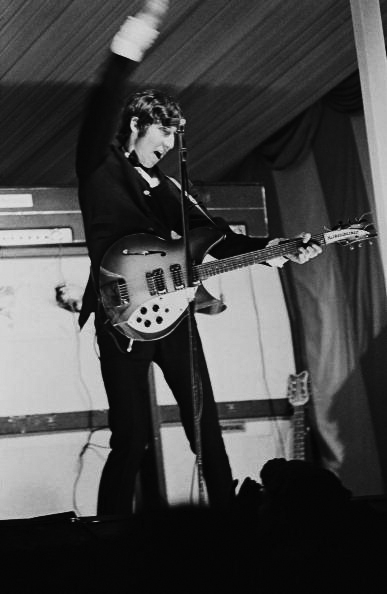

Click to view larger version. Ca. 1964, as the High Numbers, Pete with his first 1998, fitted with a Gibson ES-175 “zig-zag” tailpiece, and additional control on lower bout.

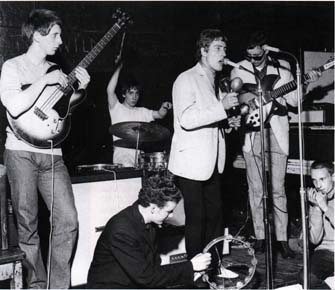

As the High Numbers in mid-1964, likely Pete’s first 1998, fitted with a Gibson ES-175 “zig-zag” tailpiece. This guitar appeared in the infamous “Maximum R&B” Marquee Club poster. Amp is a customized Fender Pro head.

Pete’s likely original Rickenbackers: 1964 360/12 “Export” and 1964 Rose, Morris Co., LTD, 1998 with a Gibson ES-175 “zig-zag” tailpiece against the wall. Speaker cabinet is Marshall 4×12, topped by Fender Bassman amp.

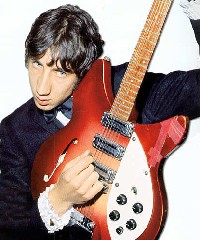

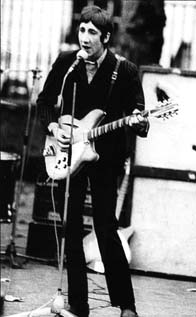

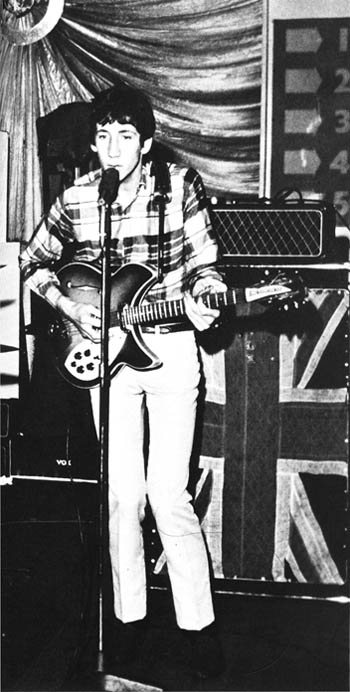

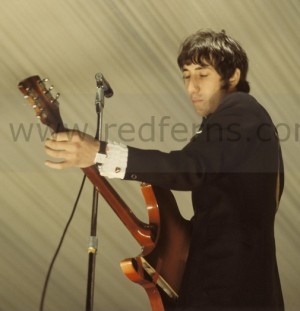

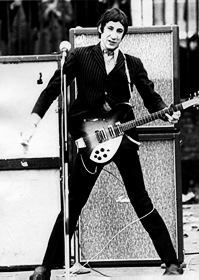

3 Aug. 1965, television performance (Daddy Rolling Stone) with 1964 Rickenbacker 360/12 “Export.” Amp is Vox AC-100.

22 July 1964 at the Scene Club, Pete plays Rose Morris, Co. LTD., Rickenbacker 1998 fitted with trapeze tailpiece from Gibson EDS-175, through Fender Pro “head” and early Marshall 4×12.

Click to view larger version. Ca. August/September 1964, at the Railway Hotel, Rose Morris, Co. LTD., Rickenbacker 1998 fitted with trapeze tailpiece from Gibson EDS-175. Amp is Fender Pro head on top of early Marshall 4×12.

1965, with 1993 and Vox AC-100.

2 June 1965, Club au Golf Drouot, Paris, with Fender Bassman top and 2×15 cabinet.

2 June 1965, Club au Golf Drouot, Paris, playing what appears to be a 1993, with Vox AC-30, left, and Fender Bassman top and 2×15 cabinet.

2 June 1965, Club au Golf Drouot, Paris, with two Vox AC-30s, left and far right, surrounding a Fender Bassman top and 2×15 cabinet.

25 March 1965, at Blue Opera R&B Club in Edmonton, North London, Rickenbacker 360/12 Export 12-string, with 1997 or 1998 6-string at right on table. Amp is Fender Pro head on top of single Marshall 4×12 on stand (with torn speaker grille cloth).

Ca.1965, Fender Bassman top on two Marshall 4×12s. Guitar is 1964 Rickenbacker 360/12 Export.

Click to view larger version. Ca. 1965, grinding a 1964 Rickenbacker 360/12 Export into an early “stack” of Marshall 4×12 cabinets powered by a Fender Bassman atop the stack, which is daisy-chained to a custom Fender Pro head at lower right.

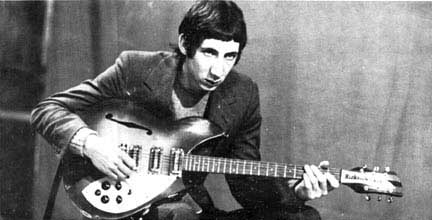

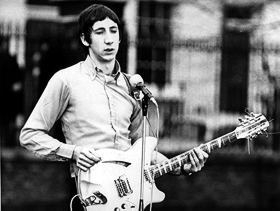

“Beat Instrumental Portrait Gallery: Peter Townshend” with 1993.

Ca. January 1965, with 1964 360/12 “Export” 12-string, through early Marshall JTM45/4×12 stack.

Ca. 1965, with 1964 360/12 “Export” 12-string.

19 June 1965, at the Uxbridge Blues and Folk Festival, with 1964 360/12 “Export” 12-string and Vox AC-100 amps. Courtesy SoundCityChris.

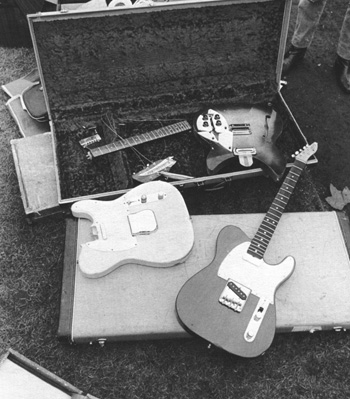

Ca. 1966, a collection of broken guitars, including two Fender Telecasters and a Rickenbacker Rose Morris 1997.

Ca. 1966, Rose, Morris Co., LTD, Rickenbacker 1993 12-string with significant repairs to the headstock.

Ca. 1966, Windsor, Rose, Morris Co., LTD, Rickenbacker 1998 with taped repair to the lower bout.

In July 1966, 6th National Jazz and Blues Festival, Windsor, two Marshall 8×12 cabinets, with tape-repaired Rickenbacker 1998.

Ca. 1966, with broken Rose Morris Rickenbacker 1997.

12 Nov. 1966, with 1965 or 1966 Rose Morris Rickenbacker 1998. Amps are Marshall (8×12 at left, 1982A and 1982B at right).

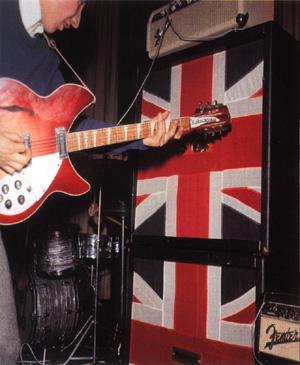

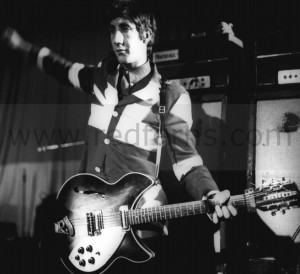

12 Nov. 1966, with 1965 or 1966 Rickenbacker 360/12 Mapleglo, previously owned by Graham Nash.

12 Nov. 1966, with 1965 or 1966 Rickenbacker 360/12 Mapleglo (previously owned by Graham Nash), and Rickenbacker Rose, Morris, Co. LTD., 1998 leaning against the cabinet, which are Marshall (8×12 at left, 1982A and 1982B at right).

Ca. 1967, backstage with Rickenbacker 360/12 Mapleglo, previously owned by Graham Nash.

3 Oct. 1966, in CBS studios, John holding French horn. Leaning against the chair, the 1962 Fender Precision Bass, left, and on the floor, the 1966 “Slab” Fender Precision Bass. Guitars are two Rickenbacker Rose, Morris Co. LTD, guitars, a 1998 and 1993. In background, two Marshall 8×12 cabinets for the guitar and bass.

23 Oct. 1966, Malmo, Sweden, late use of a Rose Morris Rickenbacker, a 1997. Guitar at left is Fender Telecaster.

Later use

1980–1981

In the studio, with Gibson J-200 and 1964 Rickenbacker 330S/12, as used on Face Dances.

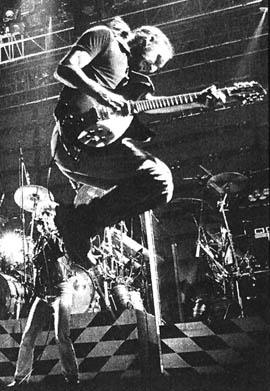

On stage with JetGlo 12-string Rickenbacker at Zurcher Hallenstadion, 28 March, 1980. Photo courtesy drjazz.ch.

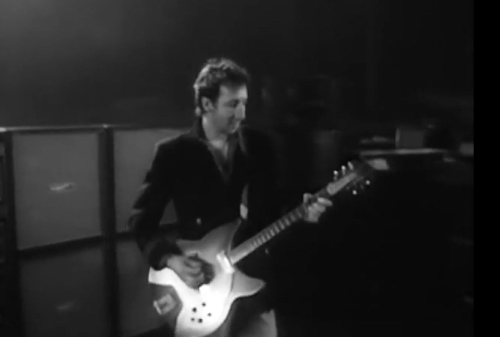

Ca. 1981, promotional video for Don’t let Go The Coat, with Fireglo 12-string Rickenbacker.

1989

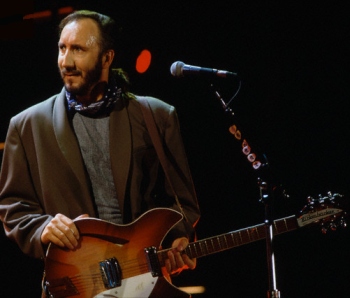

Pete used Rickenbacker 12-strings on I Can’t Explain, Substitute and My Generation in the 1989 set, played through a Mesa-Boogie Studio Preamp.

Ca. 1989, with reissue Rickenbacker Fireglo 330/12.

Ca. 1989, with reissue Rickenbacker Fireglo 330/12.

Ca. 1989, 360/12V64 12-string reissue.

Smashed 360/12V64 12-string. Pete reportedly accidentally destroyed this guitar. It was pictured on 1990’s Join Together cover, and Psychoderelict-related releases. It was on display in 2009 at the Henry Ford museum in Dearborn, Michigan, USA.

1993

Pete used a Pete Townshend Limited Edition 1997PT and a 360/12V64 12-string in the studio for Psychoderelict.

Ca. 1993, on stage with 360/12V64 12-string.

Ca. 1993, on stage with 360/12V64 12-string.

Resources and Information

Acknowledgments

- Jake Kety

- Max The Mod

For more information:

- Björn Eriksson’s Rickenbacker Info: rickbeat.com.

- Vintage Guitars Info: guitarhq.com/rick.html.

- Max The Mod: westminsterinc.com/who1965/equip.htm. (offline).

- Rickenbacker Registration: rickresource.com.

- alt.guitar.rickenbacker FAQ: faqs.org/faqs/music/guitars/rickenbacker/

Books:

- Rickenbacker, by Richard R. Smith, 1987

- The Rickenbacker Book: A Complete History of Rickenbacker Electric Guitars, by Tony Bacon and Paul Day, 1994

Manufacturer:

- Rickenbacker: rickenbacker.com.

- Pyramid Strings: pyramidstrings.com